How systems thinking exposes organisational blind spots – and what we do about them

This post sits alongside ‘What can it do?‘, another reflection on the gap between designed intention and lived performance. Where that piece explored the urgency of creative problem-solving in the moment, this one zooms out to look at the structural tensions that make those moments necessary. In both, the mantra holds: “I don’t care what it was designed to do. I care what it can do”. Whether you’re duct-taping a CO₂ filter in a crisis or bridging siloes in a modern business, it’s about situated judgement, pragmatic intervention, and ethically grounded action in the face of systemic friction.

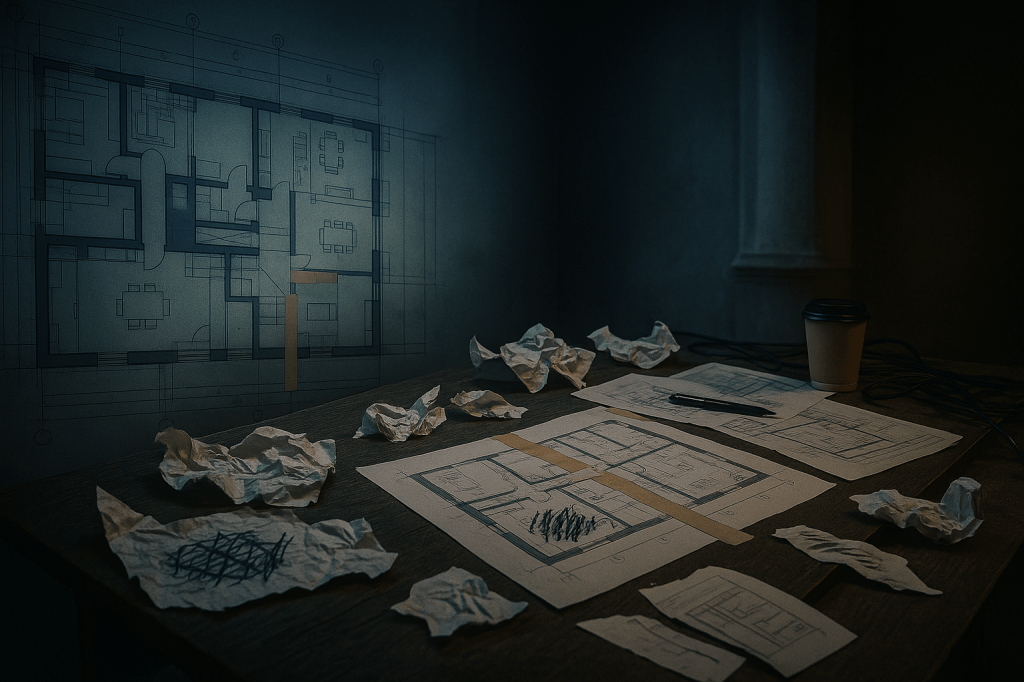

Blueprint vs building

Why insisting on how something was meant to work often gets in the way of making it work

There’s a moment that keeps repeating. Not the same words, but the same posture. I’ll be sharing a change we’re trying to introduce – a new way of capturing insight, or supporting teams, or closing a loop that’s long been left open – and someone will frown and say:

“But we already have a system for that.”

Or:

“That’s not our job, that’s HR’s responsibility.”

Or even:

“That’s just not how this part of the business works.”

And I get it. These aren’t bad people. They’re not trying to be obstructive. They’re trying to make sense of something that feels unfamiliar. To orient around the systems and remits they’ve been told to trust. But when those systems don’t actually do what’s needed – or take years to evolve – what then?

This is where the trouble begins. Because waiting for the ‘official’ process to catch up often means nothing changes. And yet stepping in to solve something that’s not officially yours to solve can be seen as presumptuous, even disruptive. It feels like going against institutional grain.

And maybe it is.

But here’s the dilemma: when the grain is misaligned with reality – when the blueprint doesn’t match the building – are you serving the system by following it, or by adjusting in the field?

A system is not its design

This tension has been with me ever since I began studying systems thinking. Early on, I encountered Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM), which describes the ‘systems‘ that map out the roles and relationships that an organisation needs in order to stay viable. It’s neat, elegant, and conceptually powerful.

But what stuck with me wasn’t the model’s structure. It was the way failures often emerge – not in the formal design, but in the connections. The interface between ‘System 3‘ (internal governance) and ‘System 2‘ (coordination). The blurry edge between ‘System 5‘ (policy) and ‘System 4‘ (strategic intelligence). The failure of one part to inform, adapt, or hear another.

It’s at those seams that many real-world interventions are needed – not because we want to redesign the whole system, but because something vital is leaking through the gaps. If we’re too purist about roles and boundaries, we miss the opportunity to intervene meaningfully.

Bridging what the blueprint forgot

In some of my current work, I’m deliberately creating temporary structures and initiatives that bridge those gaps. I’m not pretending these new pieces are permanent. But I know they are necessary.

In a way, I’m patching what the blueprint doesn’t cover – enabling the system to function in reality, not just in theory. And yes, that means doing things that don’t fit cleanly into one remit. Yes, it means treading on some toes. But I’d rather do that than let an entire initiative fail because it relied on a system that isn’t fit for purpose.

This isn’t rebellion. It’s responsiveness.

Sometimes we treat organisational structures like sacred artefacts – fixed, inviolable, not to be tampered with. But they’re not sacred. They’re scaffolds. They’re attempts at sense-making. And they only serve us if they work.

So when I hear someone say “But this system wasn’t designed to do that,” I find myself, mentally at least, coming back to that Apollo 13 line.

Not because I dismiss design. But because systems live in practice, not in principle. And my role isn’t just to preserve what was intended. It’s to enable what’s needed.

What we’re building isn’t always what was drawn

This doesn’t mean anything goes. Ad hoc fixes and rogue initiatives can cause chaos too. But there’s a difference between reckless disruption and thoughtful, systemic responsiveness.

The point isn’t to undermine the plan. It’s to honour the purpose that the plan was trying to serve.

And sometimes, doing that means deviating from the blueprint. Not because the blueprint was wrong – but because the building changed while we weren’t looking (…but also sometimes the blueprint was wrong, or impractical, or overly idealistic). The people moved in, the needs shifted, the conditions evolved. And if we want the system to stay viable, we need to adapt too.

That’s not defiance.

That’s stewardship.